What You Need to Know About Blue Light and Health

Light is a ubiquitous health variable that few understand and many dismiss.

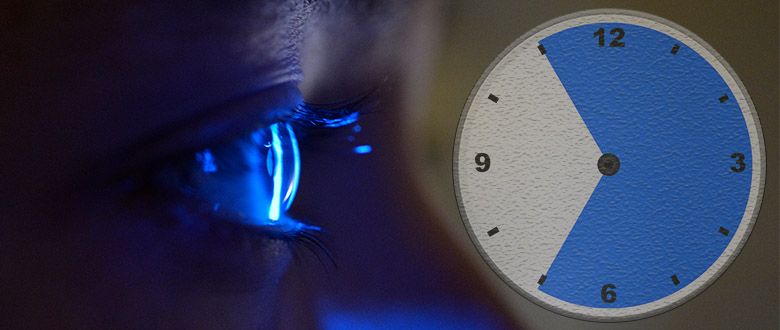

Light is a ubiquitous health variable that few understand and many dismiss. Why does light deserve our attention? Consider this: every cell in your body is tied to CLOCK genes. The name fits these genes — they act like little cellular clocks, keeping track of the time of the day. Their primary environmental time cue is light.

Your body has trillions of cells, which means trillions of clocks. They communicate with one another to keep track of your circadian rhythm, which ultimately governs every aspect of your biology, from body temperature to hormone regulation to cell regeneration.

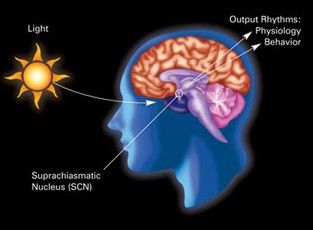

The master timekeeper of these trillions of clocks that keeps everything in sync is a mass of 20,000 nerve cells in the hypothalamus of your brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).

Given that coordination between cells (and, in turn, their clocks) is so crucial, it’s unsurprising how research continually turns up health problems tied to disorders in circadian rhythm. Did you know that:

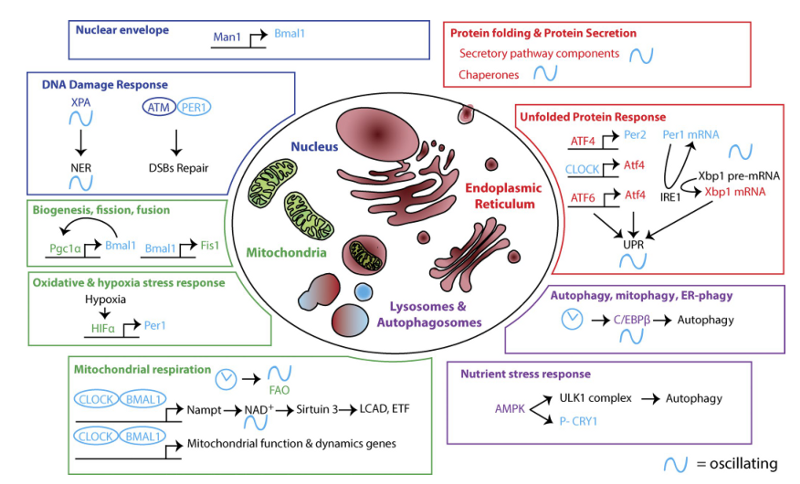

- Proper sleep suppresses inflammation via the BMAL1 CLOCK gene?

- When CLOCK genes like PER2 and BMAL1 get uncoupled, lung tumor formation is more likely?

- If CLOCK genes like BMAL1 and REV-ERBα don’t function correctly, cells can’t rest, which allows cancer to replicate more quickly?

- Artificial blue light — regardless of time of day — alters glucose metabolism (blood sugar) and sleep cycles?

There is a specific field in medicine — called chronopharmacology — that looks at the interactions between drugs and CLOCK genes. Timing matters when introducing agents into biological systems. For example, did you know that whether a mouse administered e. coli lives or dies depends on the time of day of the injection?

The simplest analogy to your body’s circadian rhythm is a symphony. The orchestra are your trillions of cells. The conductor is the SCN. When everything sync ups, you get a beautiful song — the composer’s intent. When people start playing in different times, out of tune, etc., you lose the song entirely.

With an actual symphony, the toll paid for an “off” performance is a bad song. When it comes to biology, the penalty is poor health and disease states — whether it be cancer, more inflammation and/or altered blood glucose levels — as some of the research bullet points above show.

Understanding Sleep/Wake Cycles

Much of the research on circadian rhythm focuses on melatonin, a hormone produced in your pineal gland that helps regulate your sleep, causing drowsiness at appropriate times. It should be noted that while melatonin has been called “the chemical expression of darkness” and makes sure you enter proper sleep cycles at night, it relies on light/dark cues processed by your SCN.

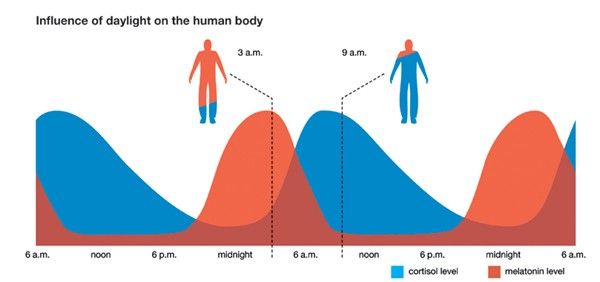

If melatonin (via the SCN) helps regulate sleep, what helps with wakefulness? That’s the role of cortisol. There’s such a surge of it first thing in the morning that that we have the term cortisol awakening response. After this surge, it slowly drops and levels off throughout the day.

In a normal person under close-to-natural conditions, you get these two bell curves you see below, with cortisol peaking in the morning and lowering toward evening, and melatonin peaking in the evening and lowering throughout the day.

How does the melatonin portion of the above chart play out at the CLOCK level? Foster and Kreitzman note in their book, Seasons of Life:

There is a very high density of melatonin receptors in the individual cells of the pars tuberalis (PT). Melatonin binds to these receptors, which alters the gene expression of several of the clock genes, including the Per and Cry genes … within the cells. … Cry gene expression tracks melatonin rise (dusk), whereas Per gene expression tracks melatonin decline (dawn).

Light: Then and Now

Notice how above the melatonin and cortisol chart, I used the words “close-to-natural conditions.” That was intentional. Up until Edison patented and commercialized the light bulb in the 1880s, we, as a species, were used to light from the sun during the day and darkness at night, or minimal, man-made light sources like candlelight and gas lamps at night, thus living under close-to-natural conditions dictated by the rising and setting of the sun.

The above picture from space shows our current nighttime reality. 54 percent of the world’s population lives in urban areas — the major source of this severe light pollution — and that number is expected to grow to 66 percent by 2050.

Research has found that 80 percent of the world’s population lives under light-polluted skies. If you narrow this down to just the United States and Europe, the number climbs to 99 percent. The virgin night sky is now so foreign to the majority of individuals that it requires going to a very remote area or a major event like a blackout to experience the night sky as intended.

The light landscape changed drastically in a very short period of time. Instead of sunlight during the day and darkness at night, most of us are bathed in artificial light almost 24/7.

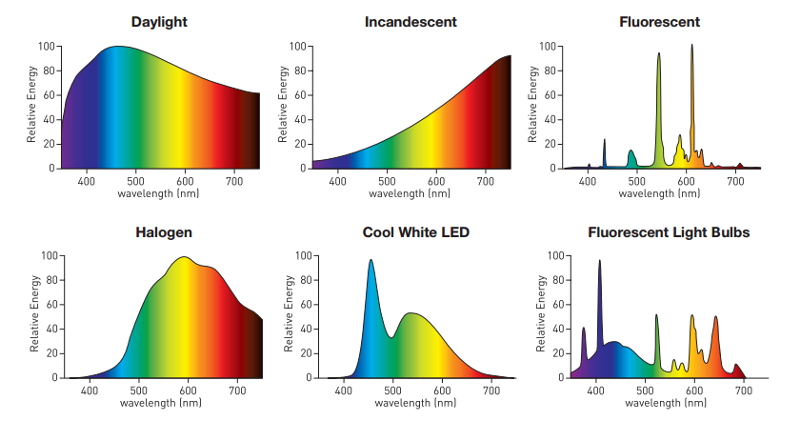

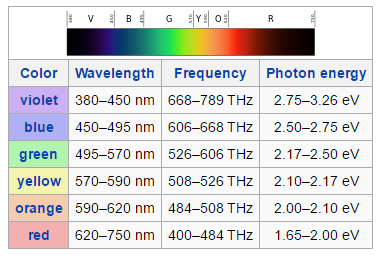

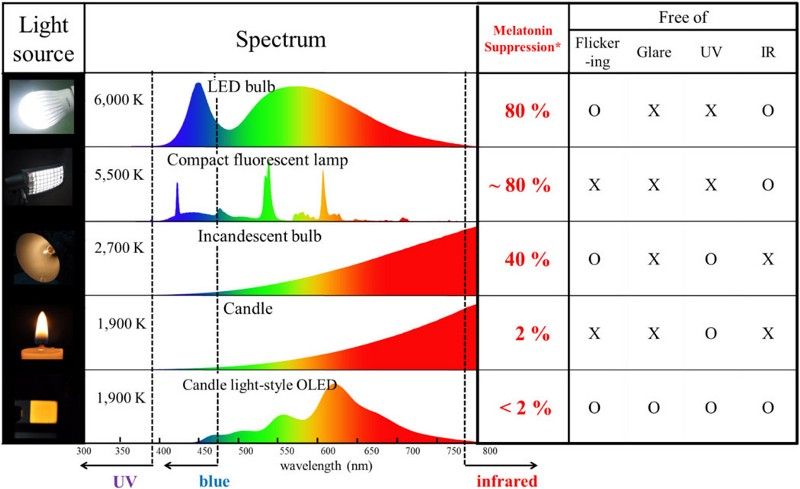

What colors are now most prevalent? If you compare the visible spectrum reference chart below to common artificial light sources above, you’ll notice we’re getting a unbalanced surplus of violet, blue, and to a lesser extent, green.

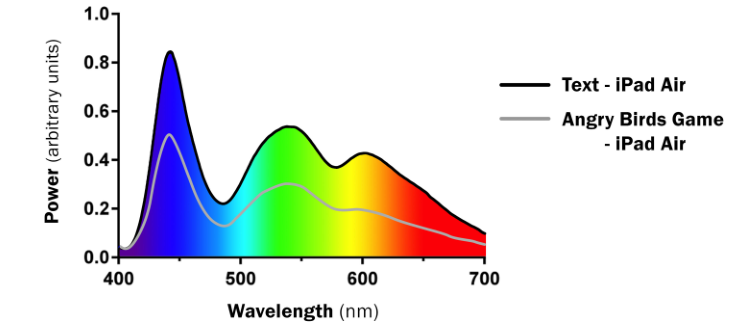

Popular devices like iPads and iPhones feature these same peaks in the violet (380–450 nm) and blue range (450–495 nm) that we see from other artificial light sources.

Melatonin: The Chemical Expression of Darkness

90 percent of Americans use light-emitting electronics within one hour of bedtime. Exposure to violet, blue and even green light (495–570 nm) after sunset has two primary effects: melatonin suppression and phase shifting or re-tuning.

Let’s cover melatonin first. As noted in the section above, melatonin helps regulate sleep. It should be obvious, but it must be stressed: we are meant to have complete darkness at night. Cell phones, tablets, TVs, overhead lights, lamps, LEDs, etc., are not natural.

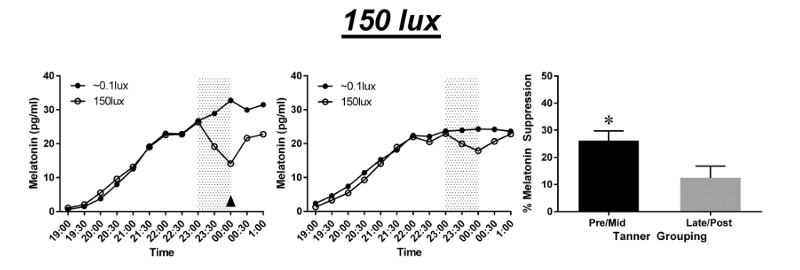

This is why studies continually find that violet and blue light suppress melatonin production the most. For example, something as seemingly innocent as room light can reduce pre-sleep melatonin levels by 71.4 percent and daily melatonin levels by 12.5 percent. This suppression effect is much greater in children than adults.

As you move further away from violet and blue (380–495 nm) toward green (495–570 nm), yellow (570–590 nm) and orange (590–620 nm) spectrum, the melatonin-suppressing effects aren’t nearly as great. Green light is about one quarter to one half as potent as blue, and yellow, orange and red have next-to-no effects on melatonin.

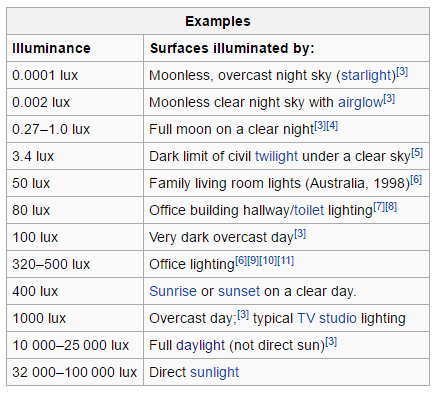

If you’ve been clicking on the research links, you’ll notice several mention the term “lux.” This is shorthand for saying the total amount of visible light present and its intensity on a surface. The higher the lux, the more intense the light source.

Complete darkness would be zero lux. As you can see above, something like a night without a full moon is only 0.002 lux. Compared to a moonless night, a typical living room light is 2,499,900 percent more intense. No, that number was not a typo.

Combine intensity (lux) with these violet, blue and green ranges (380–570 nm) and you’ve got a potent cocktail. Higher lux values amplify the damaging effects of these nanometer ranges. That’s why — if you go back to the previously cited study — you see a 301 percent increase in melatonin suppression between the 15 lux and 500 lux control groups.

When melatonin levels are disturbed and start to drop, the sleep/wake cycle is thrown into disarray and your body can’t properly utilize autophagy — an essential cellular maintenance and cleanup process. Melatonin is critical not only for this sleep/wake cycle, but the hormone itself

- Is a more effective antioxidant than vitamin E

- Reduces oxidative stress

- Makes mitochondria (your cell’s power plants) more efficient

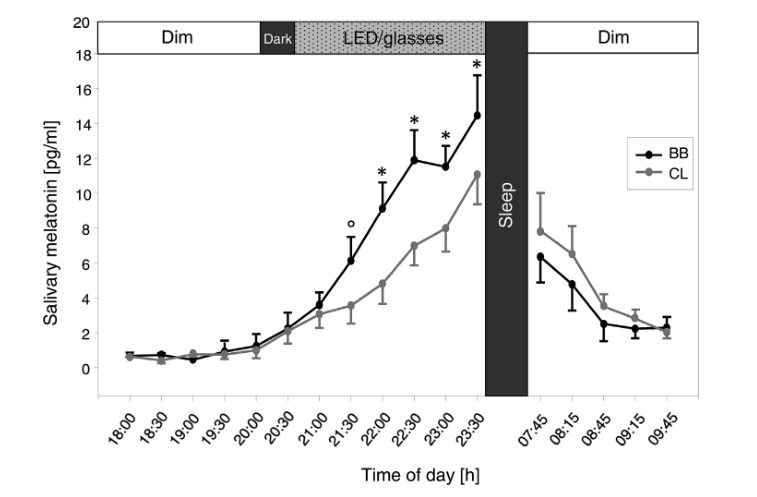

Given the melatonin-suppressing effects of violet and blue light, it should be self evident that if you block that range of light (380–495 nm) from hitting your eyes, you help preserve melatonin levels and thus keep sleep/wake cycles in order.

And that’s exactly what the research finds. Keep in mind: most of these studies only look at glasses that block violet and blue (and some green). We would expect glasses that additionally block all green to have even more benefits.

Excuse Me: What Time Do You Have?

When your circadian rhythm is running correctly, you can say you have a normal phase response curve. However, as you learned in the previous section on melatonin, violet, blue and green light start to shift sleep/wake cycles.

Organisms are so sensitive to light that just a single pulse of the wrong kind of light can initiate a process called phase shifting or re-tuning. Like with melatonin suppression, the greater the lux, nanometer range and length of exposure, the greater the phase shift.

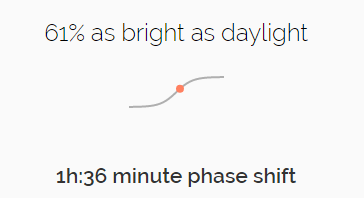

The developers of f.lux, a light-blocking software, have a handy tool called the f.luxometer that calculates the phase shift potential of different light sources.

You may be thinking, “Well, I bet it takes days, weeks, months, heck, even years, before you start to see changes at the genetic level from artificial light and phase shifting.”

Sorry to burst your bubble. As noted in the introductory section, every cell is connected to time and the greatest environmental time cue is light. We’re so wired to pick up light, that we can detect a single photon. And all it takes is one night of artificial light throwing off your sleep to alter CLOCK genes and, in turn, affect gene expression.

How do we combat this phase shifting? Per the melatonin section, any kind of barrier — like blue-blocking glasses — that stops 380–570 nm of light will help preserve melatonin and help normalize circadian rhythm. If trying to keep things dark (or as close to dark as possible) during the night helps, then the corollary should be true, i.e., sunlight during the day should help, too.

That’s exactly what Environmental Health Perspectives published:

When people are exposed to sunlight or very bright artificial light in the morning, their nocturnal melatonin production occurs sooner, and they enter into sleep more easily at night.

This should not be misinterpreted to say, “Any light is good during day.” It depends on the type of light. The above quote notes the importance of sunlight, which has a balanced spectrum. (Remember the chart from earlier?) Humans have lived under the sun’s influence for 200,000 years.

Indeed, research shows that when groups are exposed to daytime artificial light sources that are warmer and more balanced (less blue) and light sources that emphasize primarily blue, the warmer light group has circadian rhythms that more closely match the rising and setting of the sun whereas the blue light group gets entrained to unnatural rhythms:

The results confirm that light is the dominant zeitgeber [environmental cue] for the human clock and that its efficacy depends on spectral composition. The results also indicate that blue-enriched artificial light is a potent zeitgeber that has to be used with diligence.

The Eyes Have It

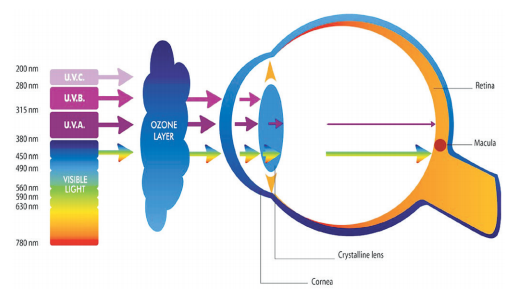

You have to understand how you see the world. Visual perception occurs when light in the 380–780 nm range hits the retina. Ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths aren’t absorbed the retina, but by the outer layers of your eyes — the cornea and lens.

As you may (or may not) remember from science class, the retinas of your eyes are packed with rods and cones. These absorb photons and convert them into neurological signals for your brain.

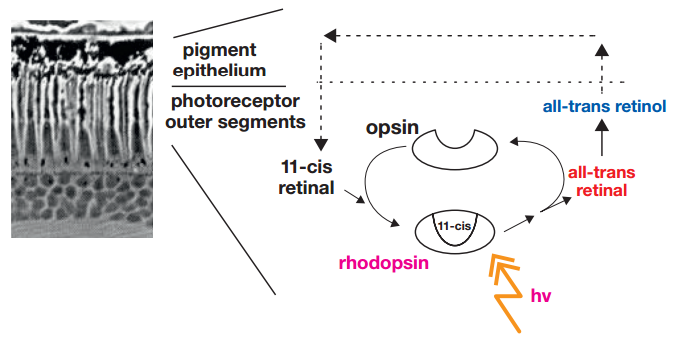

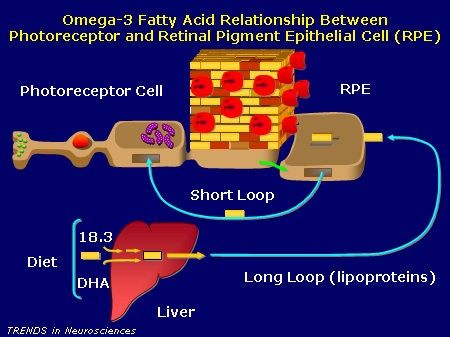

Within the retina is a light-sensitive protein called opsin. When photons hit the retina, opsin combines with other molecules to start a series of photochemical reactions, which create retinal molecules that are either stored in an area called the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) or combined with opsin again to complete the visual cycle.

That area just mentioned — the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) — is very important to our discussion moving forward. While RPE cells aren’t photoreceptive, they make sure visual pigments can regenerate and that photoreceptors survive and function normally by providing nutrients and oxygen, as well as help remove oxidized (problematic) cells.

While RPE cells don’t initiate the reactions that make the visual process happen, they do protect molecules that allow it to happen. That’s why once RPE cells start to take on too much damage, you get diseases like macular degeneration, and if enough cumulative damage occurs, blindness.

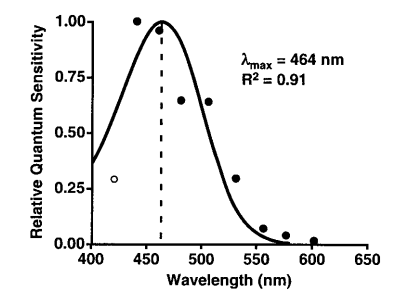

Some portion of blue light is vital to life. If it wasn’t, it wouldn’t be part of the sun’s spectrum. In fact, a photopigment called melanopsin targets the SCN to set the circadian clock. Research indicates melanopsin is most sensitive to 480 nm, which is near the end of the blue light spectrum.

How much blue (in particular, 480 nm) do we need during the day to set our clocks? More research needs to be done, but it appears as little as 30 minutes of sunlight helps with sleep quality and hormone responses, as well circadian timing.

Remember how in the section on phase shifting, we went over that not all light during the day is beneficial and that it’s better to get sunlight or try to mimic the sun rather than use artificial, blue-enriched light? The same holds true for eye health — in particular, RPE cells — regardless of time of day.

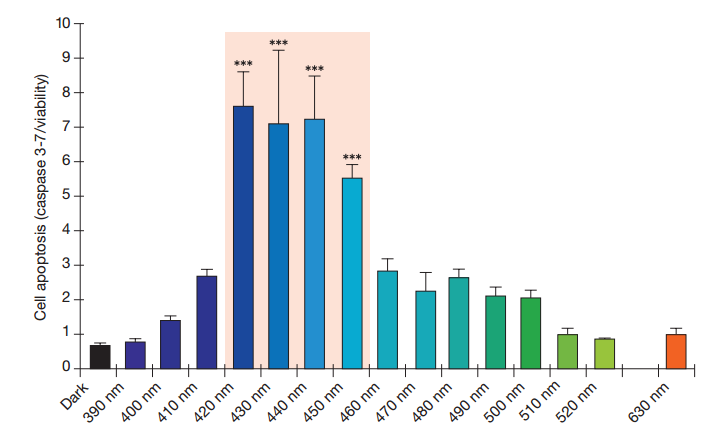

The above chart is extremely important. It shows that at all times violet and the beginning of the blue spectrum have an extremely phototoxic effect, i.e., exposure to light in that range is particularly effective at killing RPE cells.

Knowledge of this light range on retinal damage goes back to 1966. In fact, this problem is so well known in many research circles that it’s called the blue light hazard.

The obvious connection to too much damage to RPE cells we covered earlier, and that is macular degeneration. There is also one other, very significant area impacted by violet and blue light destruction of RPE cells: docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), more commonly known as the most effective portion of fish oil.

Photoreceptor cells in the retina have the highest DHA content of any cell type. And since RPE cells protect photoreceptors and actively consume DHA, it’s easy to see that if destroy RPE cells, you destroy some of your body’s greatest DHA stores.

But why should we care about DHA? Not only might DHA be necessary to completing the visual cycle, i.e., allowing you to see, but research continually finds that DHA “may indeed have a special place in biological systems.”

What makes DHA have a special place? It has been “the dominant fatty acid … for all 600 million years of animal evolution.” In fact, if we don’t get enough fatty acids, a syndrome called essential fatty acid (EFA) deficiency kicks in.

While there are many essential fatty acids, guess which one alone can completely obliterate EFA deficiency? That’s right: DHA. Not only can DHA help lower blood pressure, but it can increase the release of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which allows more chemical energy to be made available for all cells.

Given DHA’s critical place in our biology, it makes sense the upping levels helps with conditions like high blood pressure. As noted earlier, the retina has the highest concentration of DHA. Therefore, we would assume that if we keep DHA levels topped off, we would should be able to better prevent RPE-damage-linked conditions like macular degeneration, and that’s exactly what the research shows.

The DHA-retina link to circadian rhythm can be found in proteins like rhodopsin, which convert light to electrical signals in the retina, that in turn talk to the SCN. DHA enhances and protects rhodopsin whereas blue light:

Bleaches the vast majority of rhodopsin, especially at night, [and] can overwhelm the photoreceptor’s capacity to prevent damage.

It should be noted that DHA found in seafood is superior to fish oil capsules because it is not only less prone to oxidation (it’s more stable), but is better absorbed in your intestine (it’s more bioavailable) and more easily reaches your brain.